A Stubborn Silence

After my brother died last Christmas, all my instincts for resistance went into overdrive: I stubbornly wouldn’t accept it, not completely. No ripping off the bandaid for me. I was going to fight it to the bitter end, with every bit of mettle my life driven-to-overcome-being-different afforded me. I put my head down and worked. I revised and edited and beta-read before and after work.

Of course I was called upon to come up with Michael’s obituary–I was the writer after all. I cried and tried to put into a few words the best of my brother:

Mike worked as a CAD draftsman, and his passion for nature and animals inspired his family and delighted several lucky cats and dogs. Mike walked the earth in peace and his loving humor will be sadly missed. Survived by his beloved wife of 30 years. . .

But I couldn’t write what he meant to me. I couldn’t talk about the memories and put him in the past tense. I wouldn’t. I wrote his obituary but I refused to even think about his eulogy.

A Monument to Memory

I cried in private, as my whole family did. Stoic at the funeral. Had to be strong for my mom and dad. Had to be available to do all the tasks for my sister-in-law, who was understandably shattered. Numb, I supportively did the income taxes for the deceased. I obligingly designed my brother’s headstone (an oak tree on his side, two chickadees on hers).

And a few weeks later, there it was: my brother’s death was literally carved in stone.

I visited the grave at least once a week, same as my sisters, though we never went together. In the wooded town cemetery, just inside the main gate and near the monument to my 3rd great-grandfather who settled here when the town was new, I stood in snow and rain beneath a ragged hickory, a lost little sister weeping alone.

When I tried to write myself out of grief, I always wrote about my experiences now; I didn’t write about Michael, about who he “was”.

But suddenly this month all that has changed, as evidenced by that abhorrent “was” I typed with heavy deliberation in the last sentence.

The Wind Beneath My Wings

When Michael became sick and was dying of cancer, a lot of people said something that was like a bitterly cold slap in the face: “I didn’t know you had a brother.”

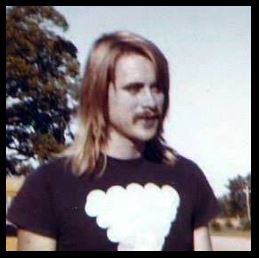

Just because he wasn’t on Facebook?! I felt hurt and I felt hollow with guilt: how could people not know about Michael? All my life he’s been with me every moment–everything I was ever interested in or enjoyed, it’s because I was following in his footsteps.

He was my hero, my inspiration, he raised me when my mom was busy with my younger sisters. He taught me to tie my shoes and to read and write and swim and climb trees and find salamanders and what the constellations were and why the moon landing was so huge. From him I learned that Star Trek wasn’t real, but it was still true.

He showed me how to plant veggies and watch wild birds and how to hammer a nail, and he took me to get my first library card. I loved exploring nature because he did. When he wrote poetry, I wanted to write poetry. Because of him I learned you could talk to animals, if your heart was in the right place.

I saw magic in everything because he showed it to me.

What’s So Bad About a Good Word

I’m ready to talk about Michael now, but I haven’t the skill to write his eulogy. I can’t write something about my brother and then put a period at the end. I’ll just have to keep telling stories of who he was before I ever was.

Michael was. He was gentle and compassionate and funny and curious. He was someone who could feed wild animals from the palm of his hand. He was the brother who could take a little Aspy girl who never got a joke and make her laugh milk out her nose. He was the teenager who graduated high school and walked across America in his knee-high moccasins.

Michael is: he’s still the biggest influence on my life, and he’s missed every day with a thousand silent agonies: sisters, mother, wife, nieces.

But from now on, that’s about all I’m going to let be silent.